Here is the completed paragraph:

Ryan Ewing

8th Grade Fitz English Section One Huck Finn Paragraph 5/20/2013 Friendship

Well, I warn't long making him understand I warn't dead. I was ever so glad to see Jim. I warn't lonesome now. I told him I warn't afraid of HIM telling the people where I was. I talked along, but he only set there and looked at me;

never said nothing. [The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapter VIII] Nothing beats spending time with a good friend. In the book, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, by Mark Twain, Huck and Jim grow to be two inseparable friends that set out on a great journey together. The two companions go through a lot over their time together, but never do they give up on each other. They are as different as people can be, physically; however, it is their similar minds that bring them together as friends. In the first couple of days after he ran away from his pap's house, Huck felt very much alone in the vast world that he was hiding in; no friends, no nothing - that was before he found Jim. One day, while Huck was out exploring the island, he stumbles upon Jim's camp; while he is appalled that Jim would run away from Ms. Watson, he is happy that he now has a companion on the island. Even though Jim thinks Huck is a ghost at first, Huck is quick to convince him that he is not:

Well, I warn't long making him understand I warn't dead. I was ever so glad to see Jim. I warn't lonesome now. I told him I warn't afraid of HIM telling the people where I was. [The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, Chapter VIII] Huck declares a friend as someone who he can trust; by saying that he was not scared of Jim telling on him, he is showing that he trusts Jim as a good friend. He knows that Jim is the kind of person that would comfort him and give him good company - that is exactly what a good friend does. Huck is white kid who hasn't quite yet developed feeling for others. Jim, on the other hand, is a slave; however, their similar taste for adventure is what ultimately makes them friends. Throughout the rest of the novel, Jim and Huck remain close friends. They realize that neither of them could have evaded capture for so long if it weren't for their friendship. For Huck and Jim, their friendship has allowed them to succeed and thrive together.

|

Preamble

Literary analysis is a type of writing where a writer literally breaks a story down to its most basic elements and then analyzes how and why those elements work in that particular story. These elements include identifying important themes, comparing and contrasting stories and authors, defining writing techniques and devices—and anything else that relates to the way in which a story is structured and told. Literary analysis deals only in what can be proved objectively via the text, and not because how and why a certain story makes you—as an individual—think and feel subjectively about that story. The Literary Analysis Paragraph #1 is designed to help any writer find and explicate the major themes in a story and to define the importance of these themes in the story. Writing an analysis paragraph is a bit like going to the doctor: you really hope that whatever your doctor finds, another doctor would find the same thing. In short: a literary analysis is simply a search for and an explaination of the "truth" of a piece of literacture.

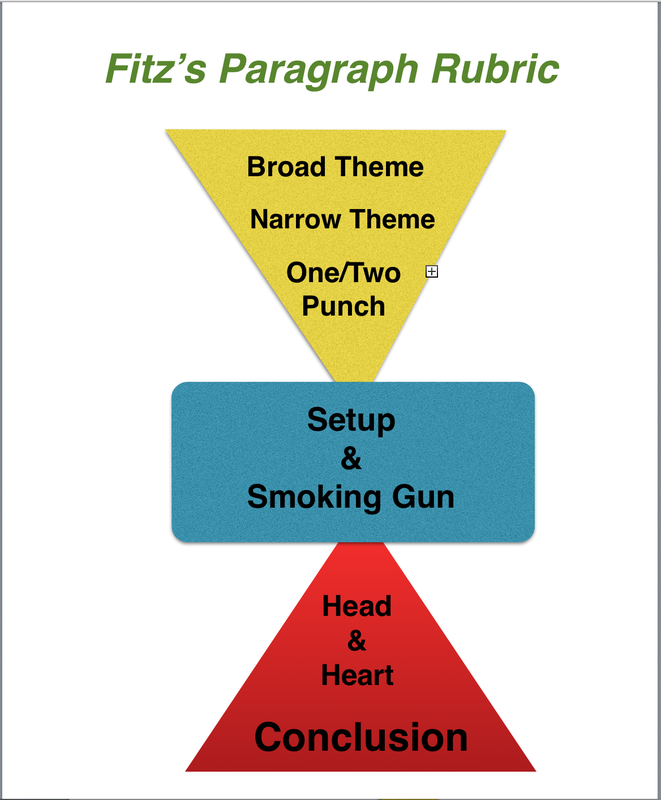

The fact that you, as the analyst, are dealing with objective and provable facts is the main reason why most teachers forbid the use of the “I” voice in this type of writing. It is here where I make the distinction between literary analysis and literary reflection: a literary reflection “reflects” your unique emotional and intellectual response to the story; whereas, a literary analysis “analyzes” the form, devices, style, and content of a story. In an analysis, the “I” is not needed and does not help you prove your point because the point is proved using verifiable facts. Throwing yourself into the mix just muddies the water and burdens your writing with unnecessary words and distractions. The basic structure of the literary analysis paragraph rubric is, however, essentially the same as the narrative paragraph rubric: you open with a clear and concise guiding theme or topic [broad theme, narrow theme, one/two punch]; you offer supporting facts and proof [smoking gun]; and in your third section of the paragraph, you explain and explicate how your guiding theme relates to the story [head and heart]. Finally, you “get on or get out.” If you are writing a single paragraph, you get out with a sense of finality; if you are writing a multi-paragraph essay, you may need to find a way to transition in a logical and unforced way to the next paragraph in your essay. It is important as a reader, and even more so as a writer, to be able to understand the importance of themes in a piece of literature, for exploring the themes of being human—and being connected (or disconnected) to the rest of humanity is the essential role of any writer! We don’t read because we care about a writer; and if you are a writer, you need to understand that nobody cares about “you” as a person any more than some guy living three towns over from you; however, we do care about ourselves, and if as a writer you put us in touch with a deeper side of our head and heart; if you pull on the strings of our imagination in such a way that we cry when you want us to cry, laugh when you want us to laugh, and think what you want us to think—then you have succeeded as a writer, and those people who do not care about you as a person will care about what you write, and they will beat a path to an door where they can find the pages that hold your words. The golden rule of writers is to always know what your readers want and expect—and give it to them in well-crafted writing, which almost always means well-constructed paragraphs! I love using the term “well-crafted” because it implies that writing well requires a deliberate and attentive focus. Good writing is never finished; it is abandoned. Honestly: give yourself ninety minutes to two hours to finish this. A writer’s first words are seldom his or her best words. Over the years I have read and graded thousands of these paragraphs. It is not hard to figure out who gave a damn and who didn’t. It is obvious who reads the left side of this rubric before writing in the right side. So give a damn. It works. Be sure to follow “all” of the details of the rubric explained in the rows below, and try your hand at a creating a well-crafted literary analysis paragraph. In the rubric , I use an example paragraph written by Ryan Ewing one of my 8th grade students in 2013. Replace his text with your own text and save this as Lastname Literary Analysis and upload to your dropbox on Schoology for this assignment. |

Fitz English

- The Crafted Word

- 8th Grade

-

9th Grade

- Rob Brower

- Chewy Bruni

- James Correia

- Christian Diprietrnatonio

- Anthony Duane

- Jack Eames

- Lucas Ewing

- Mickey Feeney

- Charlie Fitzsimmons

- Boyd Hall

- Hayden Galusza

- Zack Goorno

- Hal Groome

- Owen Gund

- Matt Hart

- Alex Hill

- Adam Jamal

- Kevin Kelleher

- Stephon KIndle

- Sidarth Modur

- Reid Monahan

- Patrick Ryan

- Spencer Pava

- Ben Sackett

- Ali Sheikh

- Max Solomon

- Eliot Stevenson

- Willie Swift

- Billy VanWalsum

- Conor Zachar

- Resources

- Poemminer

- Balladmonger

- Short Stories

- Novels

- Grammar

- Punctuation

- Rhetoric

- Multi-Media

- Forums

- Vocabulary

- Essays

- Rubrics

- Untitled

- Portfolio

- Banner

- Link

- Test

- Blog

- qjdqopsCJP

- Product